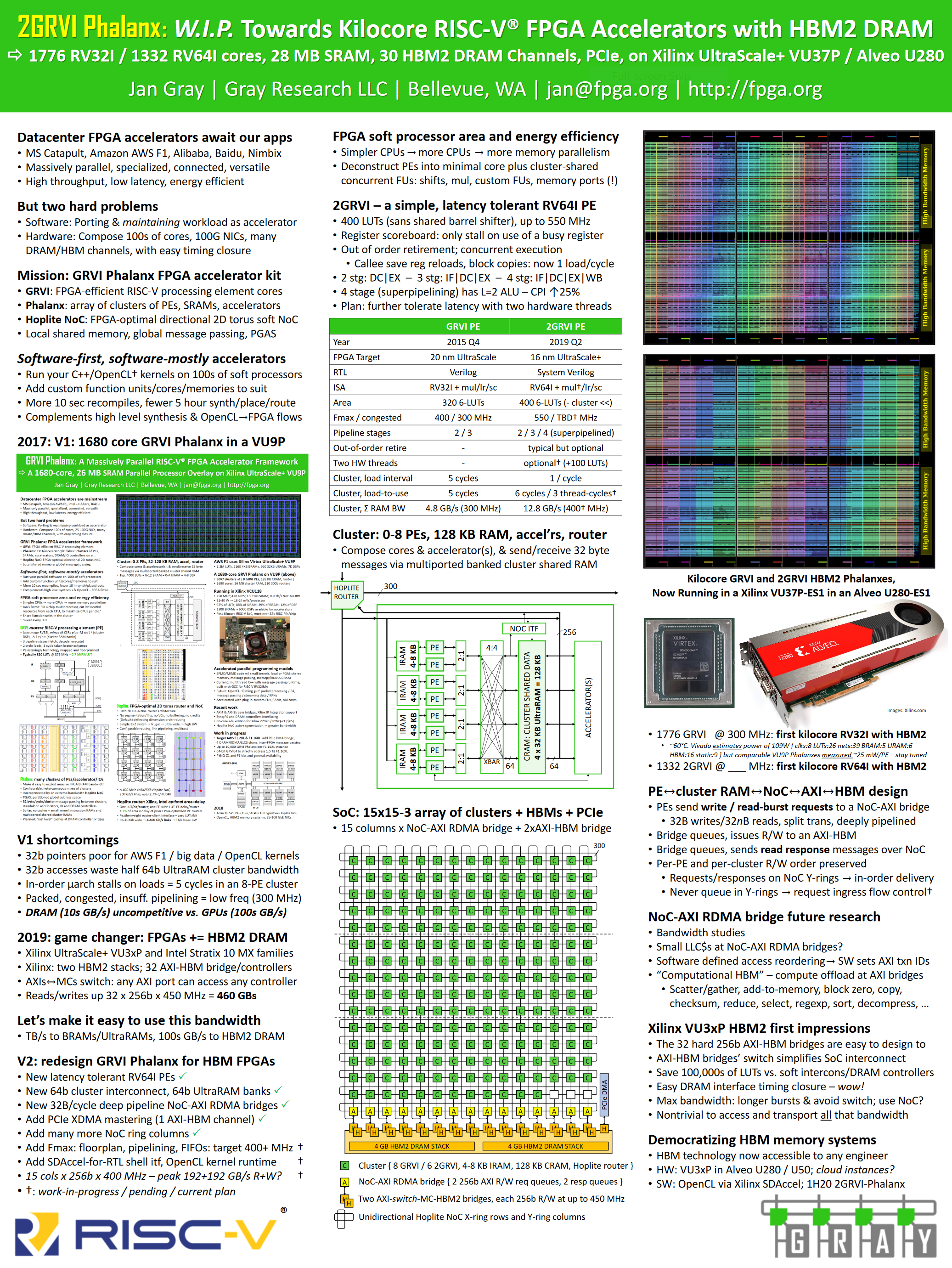

This week at Hot Chips 31 (2019) I am presenting a status update poster on the work-in-progress GRVI Phalanx Accelerator Kit: 2GRVI Phalanx: Towards Kilocore RISC-V FPGA Accelerators with HBM2 DRAM (PDF).

This is the debut of the FPGA-efficient 2GRVI (“too groovy”) RV64I processing element (PE) core, and of Phalanx support for FPGAs with HBM2 high bandwidth DRAM, first discussed last month.

The poster tells the story of the version two redesign of GRVI Phalanx to take best advantage of HBM2 DRAM. It explains some V1 limitations, particularly FPGAs’ relatively low DRAM bandwidth, and shows how the advent of HBM2 FPGAs, such as the Xilinx VCU37P and VU35P in the Alveo U280 and U50 accelerator cards, potentially with over 400 GB/s of memory bandwidth, fundamentally changes the utility and competitiveness of FPGA accelerators.

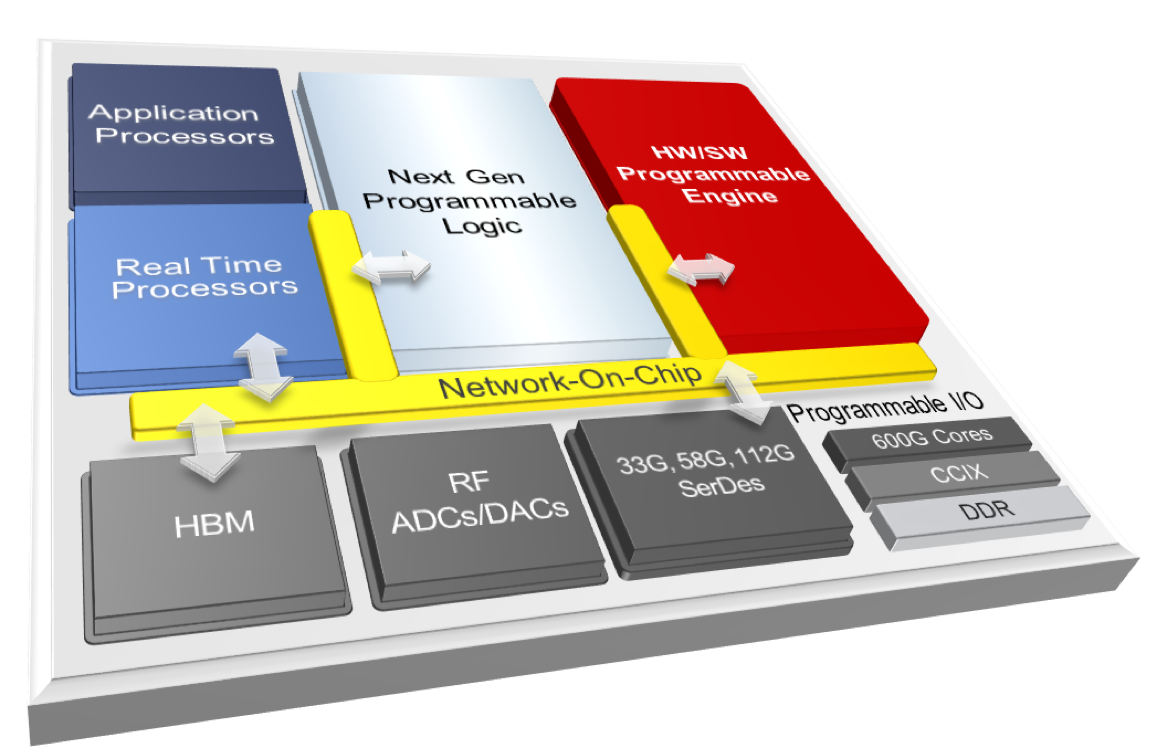

However, the Niagara of data that 30+ HBM2 memory channels can pour down on your head required changes to the PE and to the Phalanx SoC architecture to request and receive all that sweet sweet bandwidth. These changes include:

- New 2GRVI latency-tolerant RV64I PE

- New 64b cluster interconnect, 64b UltraRAM banks

- New 32B/cycle split transaction pipelined NoC-AXI RDMA bridges

- Add PCIe XDMA mastering (to an AXI-HBM channel)

- Add many more Hoplite NoC ring columns

We discuss some of these below, others in another blog post to follow.

New 2GRVI latency-tolerant RV64I 64-bit RISC-V processing element

At just 320 LUTs/PE, the good old 2016-era 32-bit RV32I GRVI PE still has leading soft processor throughput per area. Its frugality made possible the first kilocore 32b RISC processor SoCs, but GRVI’s shortcomings include: 1) its 32-bit address and data width, which is an awkward match to AWS F1’s up to 1.5 TB DRAM, to OpenCL kernels which need to pass 64-bit pointers to global memory buffers, and which wastes half of the bandwidth of 64-bit wide UltraRAM memory banks; 2) its 300-400 MHz Fmax — fast, but not fast enough; and 3) its too-simple scalar RISC microarchitecture, with blocking in-order loads. Blocking loads are fine in a one PE system with a tightly coupled BRAM memory, but in an 8 PE GRVI cluster setting a load can take five cycles there and back through the cluster interconnect to the UltraRAM cluster memory banks (which can be two long trips across one fifth of the width of the die). This is especially painful in a function epilog, reloading n callee save registers, each load taking five cycles. Ugh.

The new RV64I 2GRVI PE tackles these problems: it provides 64-bit addresses and data, up to 550 MHz pipelined execution, and latency tolerance for loads and multi-cycle function units.

Using a busy-register scoreboard, loads do not stall the pipeline until/unless subsequent use of a still busy register — so in a function epilog’s register reloads, or an unrolled block copy loop, 2GRVI issues one load each cycle. The same mechanism enables concurrent execution and out-of-order completion of long latency function units, using a to-be-proposed open Custom Function Unit interface.

As with GRVI, the 64b 2GRVI PE optionally generates RTL obsessively and exquisitely technology mapped for Xilinx 6-LUT FPGAs. It also embraces Jan’s Razor: “In a chip multiprocessor design, strive to leave out all but the minimal kernel set of features from each processing element, so as to maximize processing elements per die.” This leads to a deconstructed PE architecture where functions such as shifts, multiplies, even byte-aligning load/store memory ports, are factored out of the PE core such that multiple PEs share those occasional-use resources. This gets the 64-bit 2GRVI PE core down to just 400 LUTs, and the total area overhead of the PE and its share of a six PE cluster, function units, cluster interconnect, and 300b Hoplite router, is about 700 LUTs.

For its highest Fmax of 550 MHz, 2GRVI can implement a 4-stage pipeline with an initiation interval of one instruction/cycle, but a minimum ALU result latency of two cycles. This enables higher frequency SoC designs, but impairs CPI by 25% or so. To mitigate ALU result-use stalls and four cycle taken branches, I’m also exploring introducing two-way hardware multithreading. This will cost ~100 LUTs, +80 LUTs of which are needed to double the physical register file to 64x64b, so it remains to be seen if this is a net win from the perspective of total throughput / area. We’ll see.

In all, 2GRVI’s XLEN width doubling, load latency tolerance, and higher Fmax means 2GRVI PE clusters have double or triple the total bandwidth to the cluster data RAMs vs. the older GRVI PEs in a GRVI cluster, using the same LUTs and UltraRAMs.

The following table compares and contrasts the two cores.

| GRVI | 2GRVI | |

| Year | 2015 Q4 | 2019 Q2 |

| FPGA Target | 20 nm UltraScale | 16 nm UltraScale+ |

| RTL | Verilog | System Verilog |

| ISA | RV32I + mul* + lr/sc | RV64I + lr/sc (mul WIP) RV32I to come |

| Area | 320 LUTs | 400 LUTs (not including barrel shifter) |

| Fmax / congested | 400 / 300 MHz | 550 MHz / TBD MHz |

| Pipeline stages | 2 / 3 | 2 / 3 / 4 (superpipelined) |

| Latency tolerance: out-of-order retire | – | typical but optional |

| Latency tolerance: two hardware threads | – | optional (WIP) (+100 LUTs) |

| Cluster, load initiation interval | 5 cycles | 1 / cycle |

| Cluster, load-to-use | 5 cycles | 6 cycles / 3 thread-cycles (WIP) |

| Cluster, peak cluster RAM bandwidth | 4.8 GB/s (300 MHz) | 12.8 GB/s (400 MHz (WIP)) |

Phalanx redesign for HBM2 memory

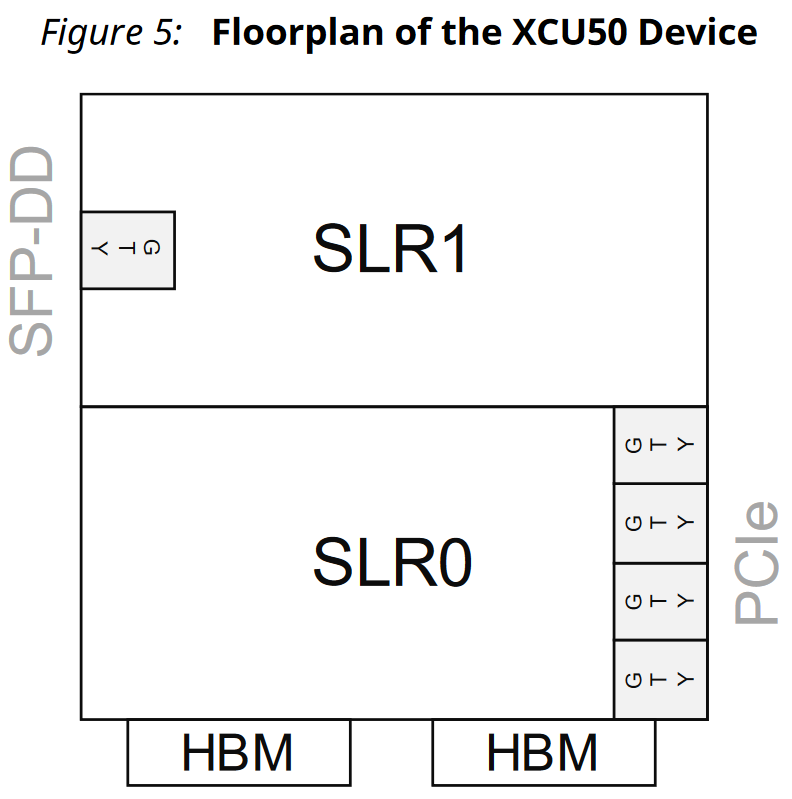

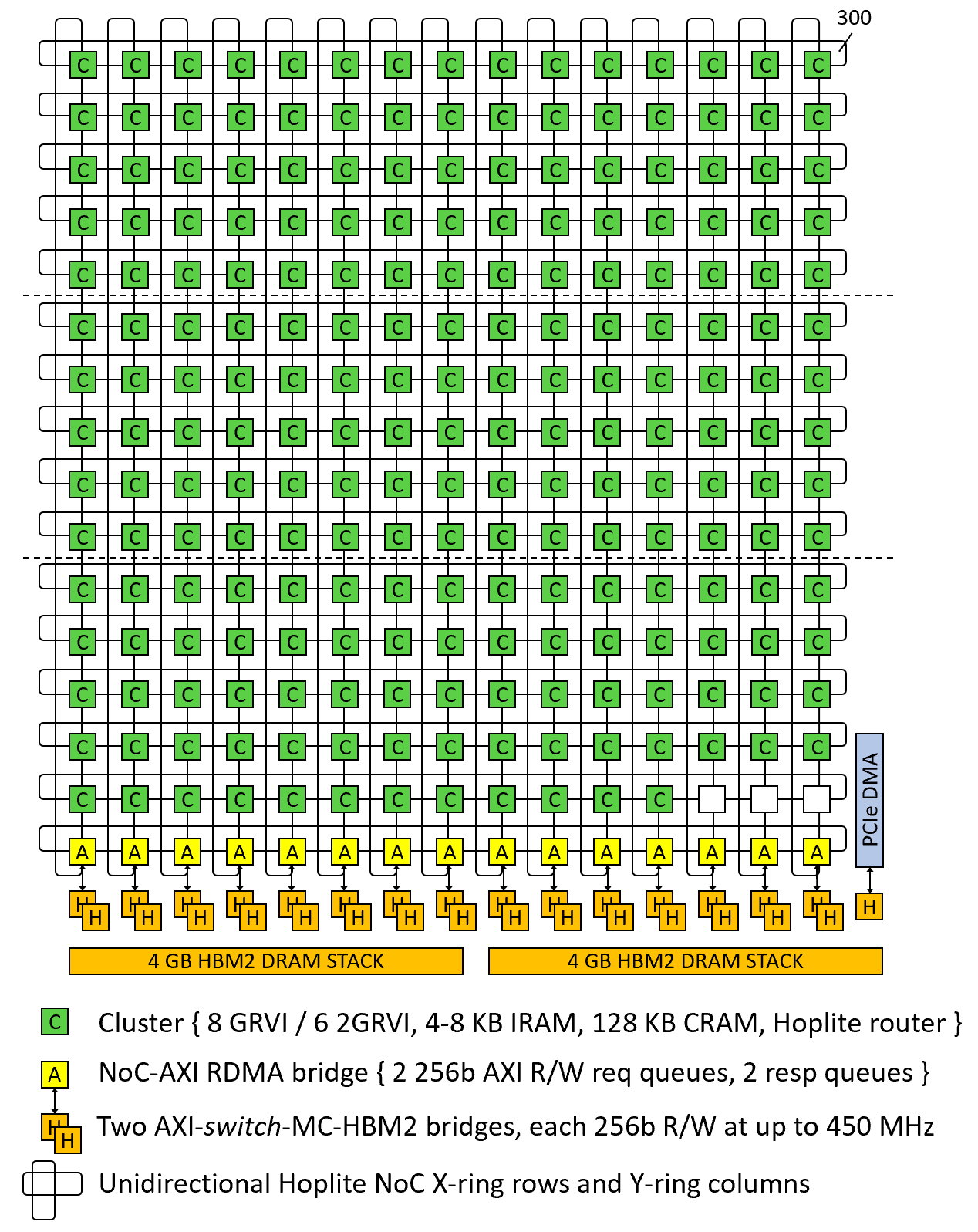

The Phalanx “array of clusters, exchanging messages on a NoC” architecture has been redesigned for Xilinx UltraScale+ HBM2 devices such as the VU37P FPGA, with 32 256b @ 450 MHz hardened AXI-HBM controllers coupled to the two stacks (8 GB) of HBM2.

It is rather tricky to move data at up to 3.7 Tb/s to/from the AXI-HBM controllers at the base of the FPGA, from/to the various cores across the length and breadth of the device. A very fast, very wide soft NoC is the way forward, although at FPGA SoC frequencies (300-600 MHz) this requires many thousands of northbound and southbound nets. (The faster the NoC clock, the fewer nets required.)

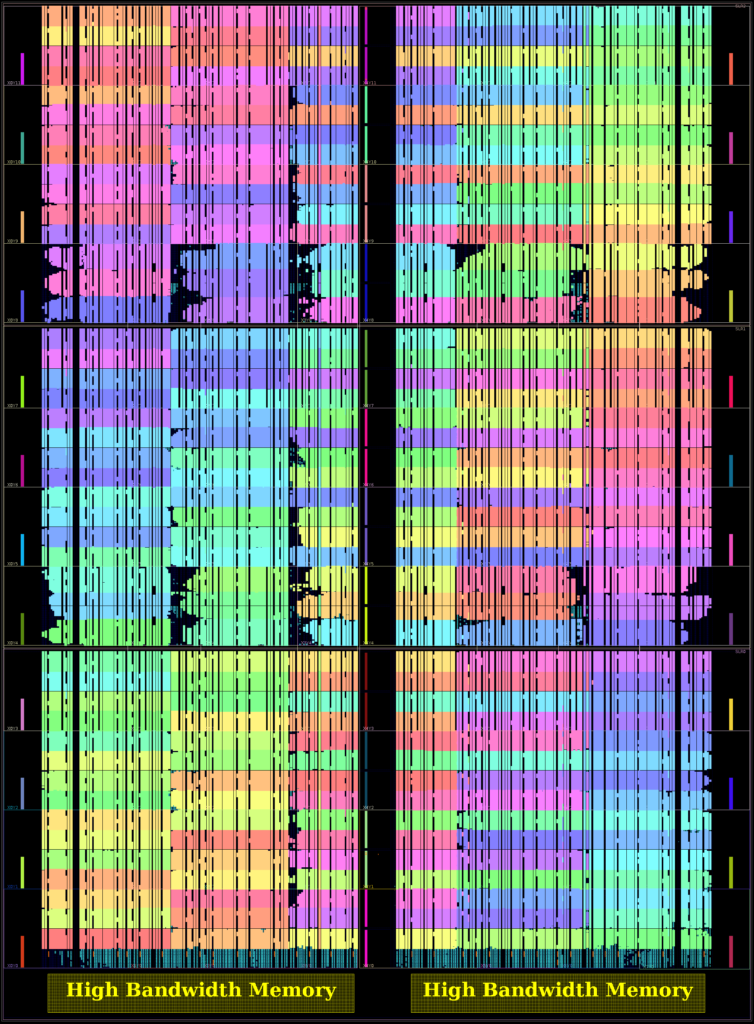

Then other clock constraints must be considered. The older 32-bit GRVI PEs are too slow; the Hoplite NoC and UltraRAMs can run at 600 MHz, but the AXI-HBM controllers’ Fmax is 450 MHz. To avoid clock domain crossings (for now) we aim to run each component at 450 MHz. (It’s a work-in-progress, we’re not there yet.) Then a 15x15x256b Hoplite NoC will carry ~200 GB/s of read data and ~200 GB/s of write data between the HBM controllers and any FPGA clusters or I/O controllers. While not yet full peak VU37P HBM2 bandwidth, it is nevertheless a giant leap ahead for RISC-V multiprocessors and for FPGA accelerators.

So this redesign depends on three advances: 1) modifying the NoC’s X rings x Y rings topology to include at least twice as many die-spanning vertical Y rings; 2) designing a wide, deeply pipelined NoC-AXI RDMA bridge that can sustain writes and burst reads on back to back clock cycles, 256 bits per bridge per cycle, all day long; and 3) generally increasing the Fmax of every element of the SoC from 300 MHz towards 450 MHz.

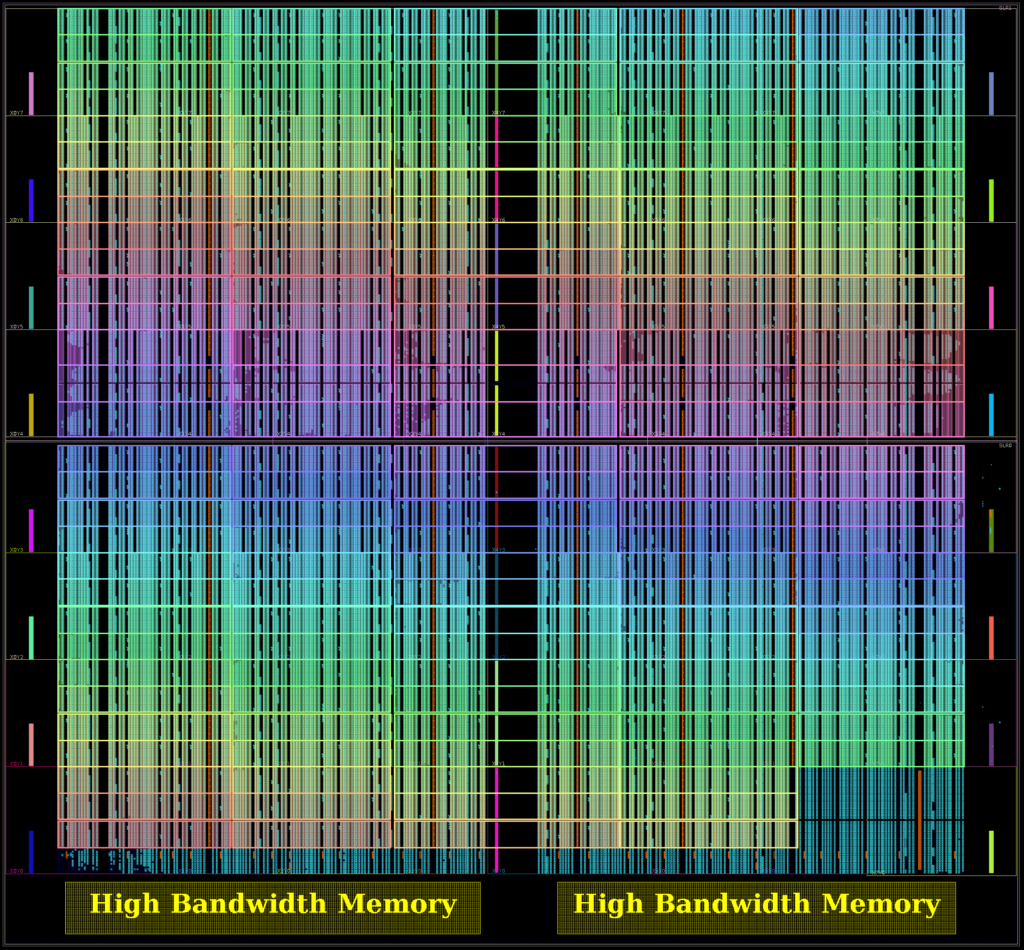

At present the first two have been achieved. The 30×7 NoC of the 2017 Hot Chips demonstration is replaced here with a 16×15 NoC with an array of 15×15 PE clusters and a row of 15×1 NoC-AXI RDMA bridges, each coupled to two AXI-HBM bridges. This doubles the NoC bandwidth to the HBM2 bridges. Here’s the new system topology:

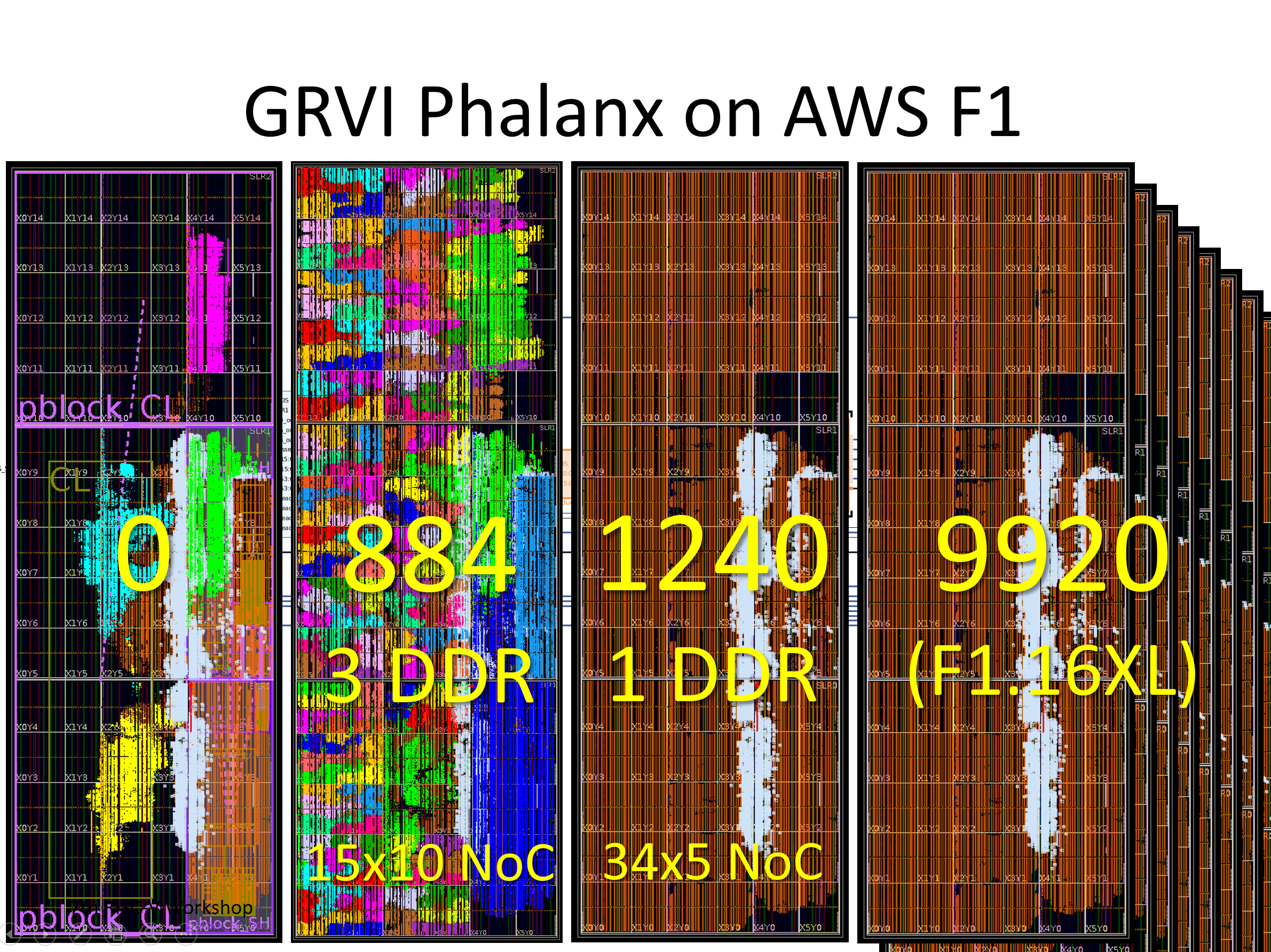

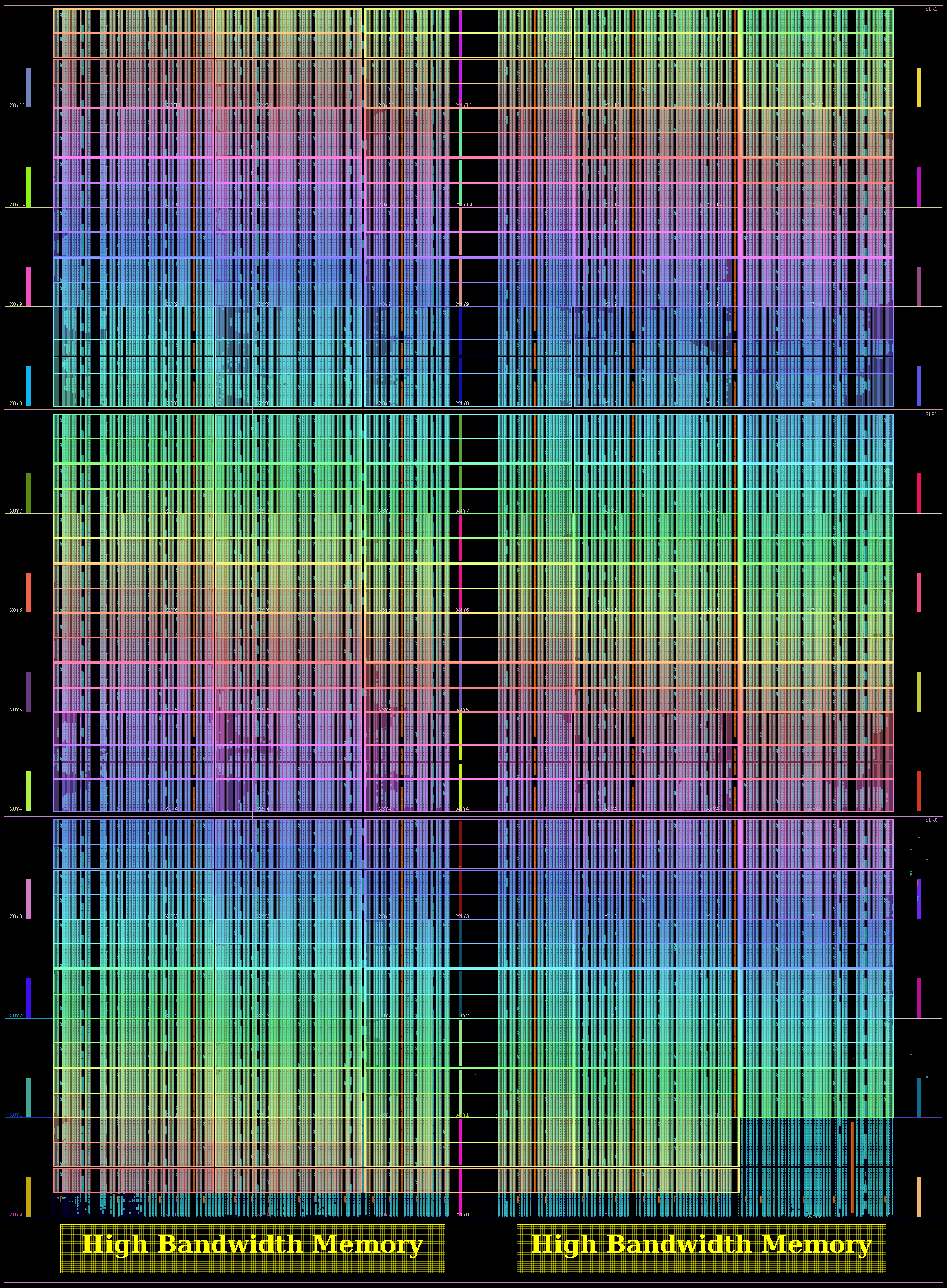

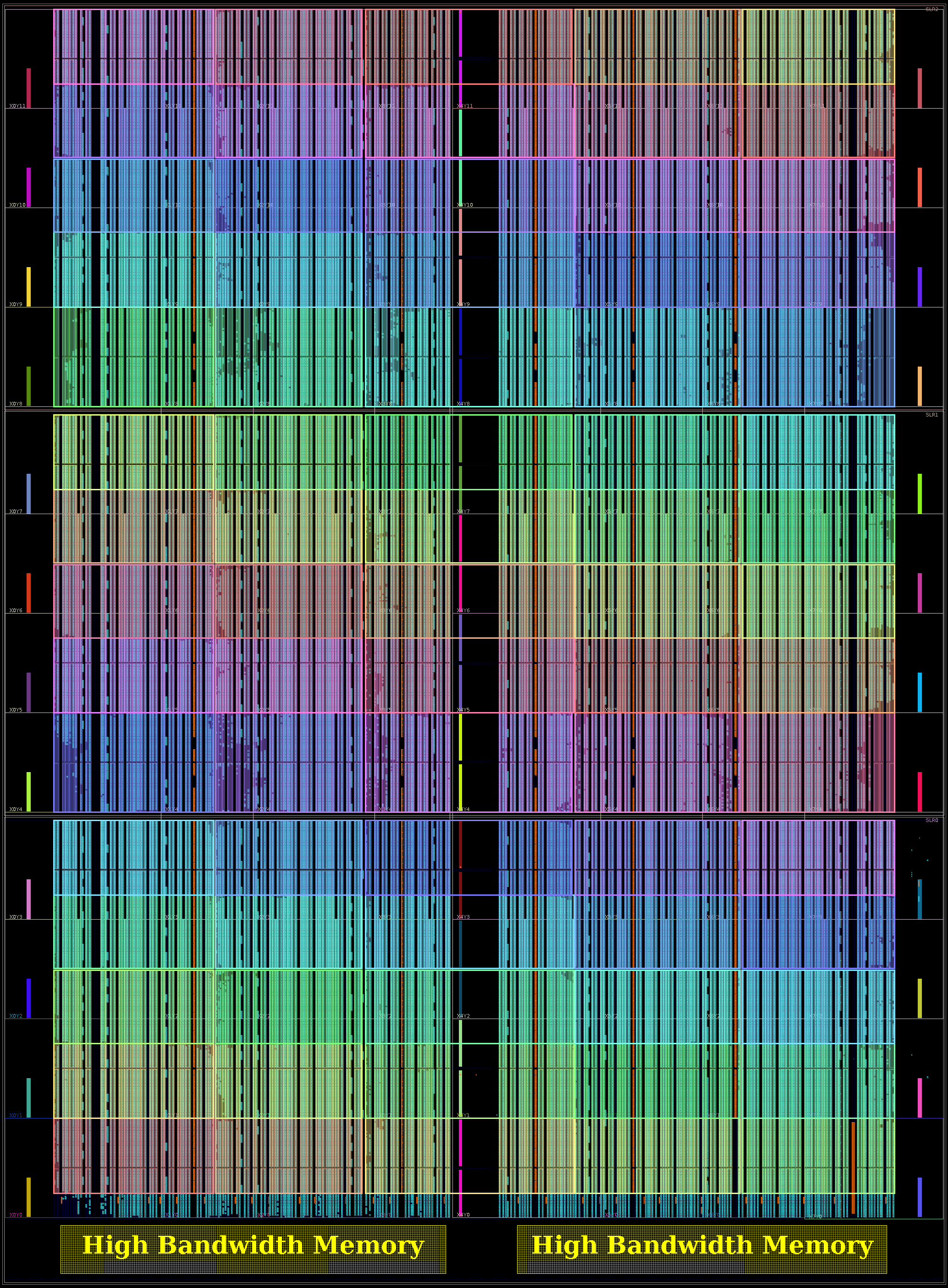

The poster presents two different FPGA SoCs design chip plots.

The first is a 1776 PE GRVI Phalanx, with (15×15-3) x 8 32-bit GRVI PEs. (It depopulates three clusters in the bottom right of SLR0, freeing up some LUTs needed for the ~15000 LUT PCIe XDMA logic.)

The second is a 1332 PE 2GRVI Phalanx, with 222 clusters of six 2GRVI RV64I PEs. To our knowledge this is the first operational kilocore 64-bit RISC SoC in any technology, and the first with HBM memory.

A later blog post will drill down into this design, how the memory system works overall, and experiences working with the Xilinx AXI-HBM bridges.