Ch-ch-ch-changes

I have returned full time to the software world; without discussing specifics, my aim is to significantly improve the lives of software developers and software users alike.

Fear not, I anticipate that this site will continue to report upon news, and muse aloud about ideas, in the FPGA CPU and SoC space. However, expect the reports to be more sporadic, and any musings to be less elaborate.

Thanks giving

To my wonderful family, thank you. How happy I am that we are here together to share life’s rich pageant.

Thanks to my friends. I am so fortunate to share friendship with some most excellent kindred spirits who are so generous with their time, regard, insights, kindness, well wishes, and good cheer. Special thanks to those several of you whom I am privileged to count as close friends. Thank you for being one in a thousand.

I thank and remember those who have gone before, who lived and worked and fought and died to make the world a happier place for this ungrateful entitlement generation. Many of us here in the western world have never known want, disease, hunger, strife, nor war in our backyard. Let us remember those that still live with these hardships.

Apropos of this site, I also thank the vast legions of hard working engineers and scientists, and their collected and focused embodiments in corporations, for ceaselessly advancing the science and the processes and the devices and the platforms and the tools and the infrastructure so as to deliver, free, the miracle of modern programmable logic, that empowers even the little guy to turn ideas into tangible hardware.

And I thank you, dear reader, for frequenting this site, warts and all.

New Xilinx Spartan-IIE devices — like manna from heaven

In September, Altera announced Cyclone, and last November, Xilinx announced Spartan-IIE. Back then I wrote,

“You might think that as Virtex-E is to Virtex, so is Spartan-IIE to Spartan-II.””But you would be wrong. According to data sheets, whereas an XCV200 has 14 BRAMs (56 Kb) and the XCV200E has 28 BRAMs (112 Kb), in the Spartan-II/E family, both the XC2S200 and (alas)the XC2S200E have the same 14 BRAMs (56 Kb).”

“If your work is “BRAM bound”, as is my multiprocessor research, this is a disappointment.”

Now Xilinx announces two new, larger Spartan-IIE devices, the XC2S400E and XC2S600E. And lo and behold, unlike the BRAM deficient XC2S300E, the 2S400E and 2S600E have the same BRAM to LUT ratios as the original V400E and V600E. Thanks Xilinx!

A good thing too, for otherwise these parts would be seriously RAM poor vis-a-vis their Cyclone competition.

Xilinx: … Extends World’s Lowest Cost FPGA Product Line.FAQ.Data sheet (alas, no single PDF).

“In 2003, the company is on track to deliver a fifth generation of the Spartan Series, reaching even higher densities at significantly lower price points.”

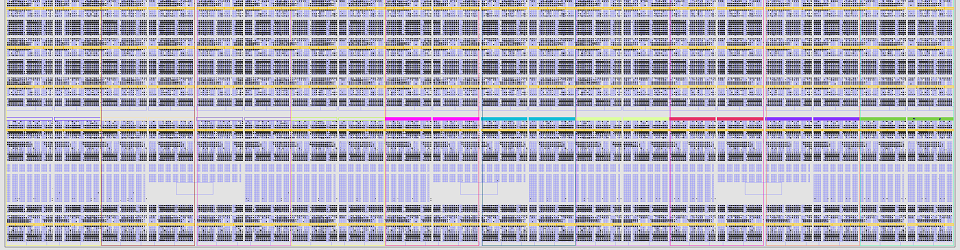

Here is the updated competitive landscape. Since Xilinx is making a big noise about the greater number of I/Os available with Spartan-IIE devices (an observation first noted by Rick “rickman” Collins), I thought I would oblige them and add a column for I/O.

(The concept of the Cyclone parts, as I understand it, is the pad ring limits determine the area of the device and hence the area for the programmable logic fabric. So what, then, does the higher ratio of I/O to logic in the Xilinx devices tell us?)

BRAM 02 03 04 03 Device Kb KLUT I/O BAP BAP BAP Ref $/KLUT

XCS05XL 0 0.2 77 $2.5 [3] $12.75

XC2S50E 32 1.5 182 $7 [2] $4.67

EP1C3 52 3 104 $7 $4 [1] $2.33

EP1C6 80 6 185 $17 $9 [1] $2.83

XC2S300E 64 6 329 $18 [2] $3.00

XC2S400E 160 10 410 $27 [4] $2.70

EP1C12 208 12 249 $35 $25 [1] $2.92

XC2S600E 288 14 514 $45 [4] $3.26

EP1C20 256 20 301 $60 $40 [1] $3.21

XC2V1000 640 10

EP1S10 752 11

EP1S20 1352 18

XC2V2000 896 22

BRAM Kb: Kbits of block RAM

(excludes parity bits, LUT RAM, and "M512s")

KLUTs: thousands of LUTs

I/O: maximum user I/O

BAP: approximate best announced price, any volume

$/KLUT: approximate 2003 BAP/KLUTs

References:

[1] Altera Cyclone Q&A:“High-volume pricing (250,000 units) in 2004 for the EP1C3, EP1C6, EP1C12, and EP1C20 devices in the smallest package and slowest speed grade will start at $4, $8.95, $25, and $40, respectively. … Pricing for 50,000 units in mid-2003 for the EP1C3, EP1C6, EP1C12, and EP1C20 devices in the smallest package and slowest speed grade will start at $7, $17, $35, and $60, respectively.”

[2] Xilinx Spartan-IIE press release:“Second half 2002 pricing ranges from $6.95 for the XC2S50E- TQ144 (50,000 system gates) to $17.95 for the XC2S300E-PQ208 (300,000 system gates) in volumes greater than 250,000 units.”

[3] Xilinx Spartan prelease:“Spartan pricing ranges from $2.55 for the XCSO5XL-VQ100 (5,000 system gates) to $17.95 for the XC2S300E-PQ208 (300,000 system gates) in volumes greater than 250,000 units.”

[4] Xilinx 2nd Spartan-IIE press release:“XC2S400E … and XC2S600E … and are priced at $27 and $45 respectively (250K volume).”

Other reports Anthony Cataldo, EE Times: Xilinx packs more I/O into its top-selling FPGA line.

Crista Souza, EBN: Xilinx drives Spartan-IIE to high end.

Peter Clarke, Semiconductor Business News: Xilinx adds two FPGAs to Spartan family.

(I think it is interesting to note that no one else picked up on the much more generous servings of BRAM ports and bits in the newer devices.)

What XC2S600E means to me Please refer back to this piece that sketches how in April ’01 I PAR’d a multiprocessor of 12 clusters of 5 processors in a single V600E, using 1 1/5 BRAMs per processor.

At the time, the V600E was not inexpensive.

Now with the advent of the XC2S600E, we can see practical and inexpensive supercomputer scale meshes of simple processing elements implemented completely and cost effectively in programmable logic.

At 60 processors per $45 device (in huge volumes), that works out to just $0.75 per processing element. Loaded up with DRAM, this implies a total component cost of ~$1.50/PE, and a density of about 20-40 processors per square inch.